Does glucose increase the absorption of fructose in the intestine?

09/18/2021 Food Intolerances

“Eat some glucose with a serving of fruit and your body will better absorb the fructose contained in the food.” Such a statement can be found on many a nutrition website, along with the claim that just one glucose tablet can remedy any digestive ailment. But is this actually the case? The idea that consuming glucose can improve the absorption of fructose makes sense in theory, since it tilts the fructose-glucose ratio in favor of glucose. In practice, however, this is not borne out by the facts.

Numerous studies confirm that consuming glucose at the same time as fructose leads to better absorption of the fructose [1]. Pure fructose alone is absorbed very slowly in the small intestine and can therefore reach the large intestine in high amounts, where it is broken down by microorganisms. By contrast, with a sugar solution that consists of equal parts fructose and glucose, the former can be absorbed through the intestinal wall much more quickly.

Common to each study, however, is that they involve pure sugar solutions, which the participants drink on an empty stomach. These conditions are necessary to ensure good comparability among the participants, but they are unrealistic when it comes to assessing glucose’s impact on fructose absorption in everyday meals.

Let us use the example of an apple to take a closer look at the digestive process. After consumption, the apple passes through various stages of the digestive tract, in order for the body to extract as many of its nutrients as possible. Digestion begins as soon as the apple is chewed, as enzymes in our saliva break down the carbohydrates. Crudely chopped and chewed up by the time it reaches the stomach, gastric acid containing further digestive enzymes then turns the apple into a fine pulp.

The pulp passes through the pylorus and reaches the small intestine, where it is mixed with more digestive fluids that break down proteins and fats. Moving slowly through the small intestine, yet more nutrients are gradually absorbed through the intestinal mucosa into the bloodstream. Other enzymes in the intestinal mucosa break down disaccharides into their individual components – glucose, galactose or fructose – that can also then be absorbed into the blood (for more on this subject, check out our blog here).

Foods pass through the digestive tract at different speeds, depending on how easily they can be broken down. For example, a piece of white bread, which is easily digestible, passes through the stomach much quicker than foods containing fats and protein. Meanwhile, beverages containing sugar pass through the stomach quickly, and the sugars they contain are then promptly absorbed by the body in the intestines. With high-fiber foods, the pulp spends more time in the stomach and its carbohydrates are released steadily over a longer period of time. The pylorus permanently ensures that enough broken-down food fragments pass into the small intestine [2].

The glycemic index is a scale from 1 to 100 that indicates how quickly a specific quantity of carbohydrates increases blood sugar levels after consumption. A high value signals a rapid increase.

▲ Table 1: Apples have a significantly lower glycemic index than glucose [3].

When determining a food’s glycemic index, glucose, having a value of 100, serves as reference point. As a monosaccharide, it is easily digestible and passes quickly into the blood stream. The digestion of a glucose tablet begins when it is chewed, since it is absorbed by the body through the oral mucosa. As glucose contains no fiber, it moves through the stomach in a matter of minutes. The absorption is complete soon after the glucose reaches the small intestine, where it travels barely an eighth of the intestine’s 8m length before passing through the intestinal mucosa and into the blood [4].

The apple is also easily digested because it contains very few fats and protein, but it passes from the stomach into the small intestine more gradually, over a period of two to three hours [5]. Its sugars are bound in a complex fiber structure, so they remain intact as the apple moves through the digestive tract, and they are released more slowly compared to pure glucose [6]. The fructose in the apple will not be completely absorbed even after it has passed through the small intestine, so a certain amount will reach the large intestine. If a sizeable quantity of fructose reaches the large intestine, digestive problems may occur.

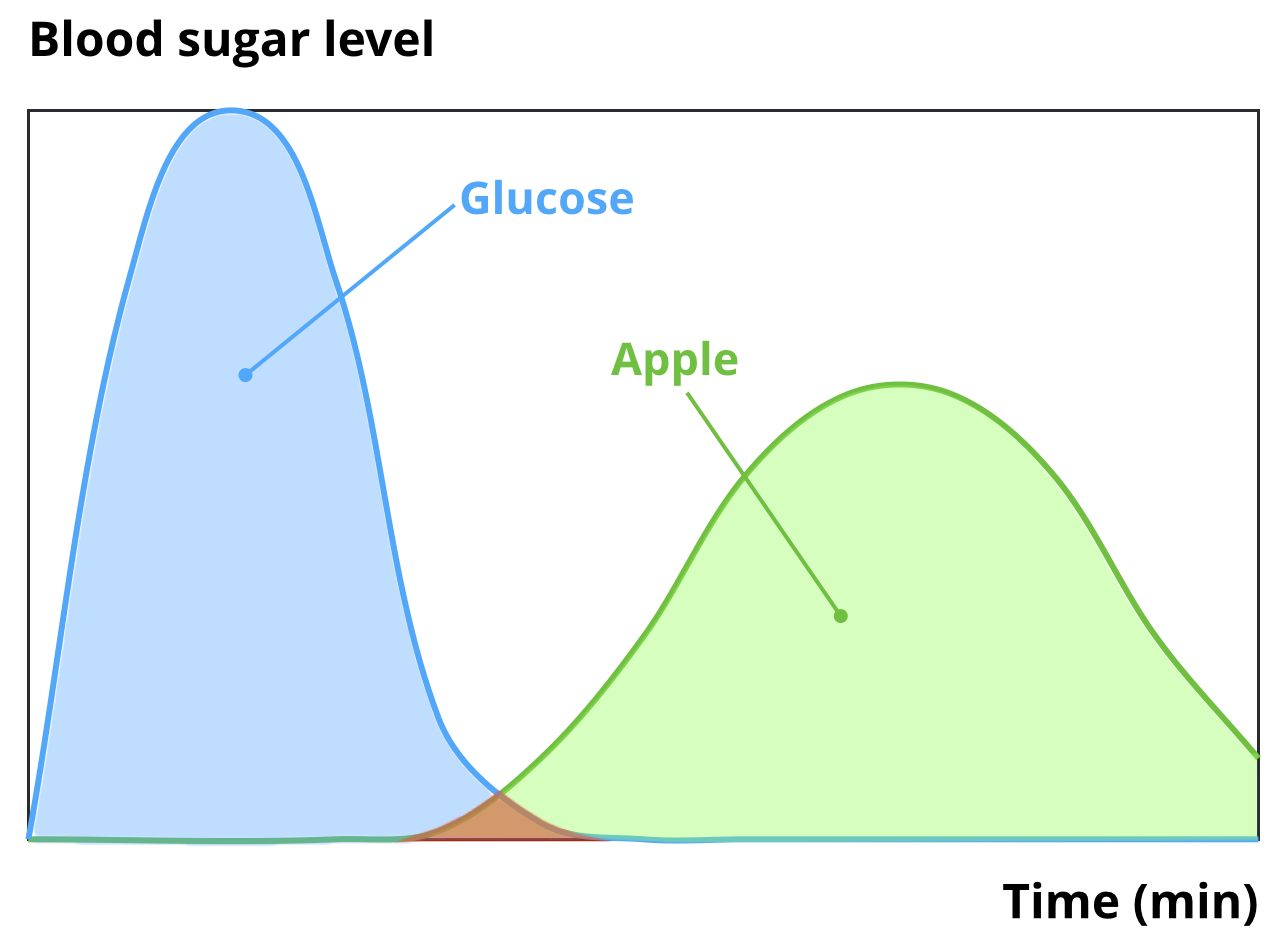

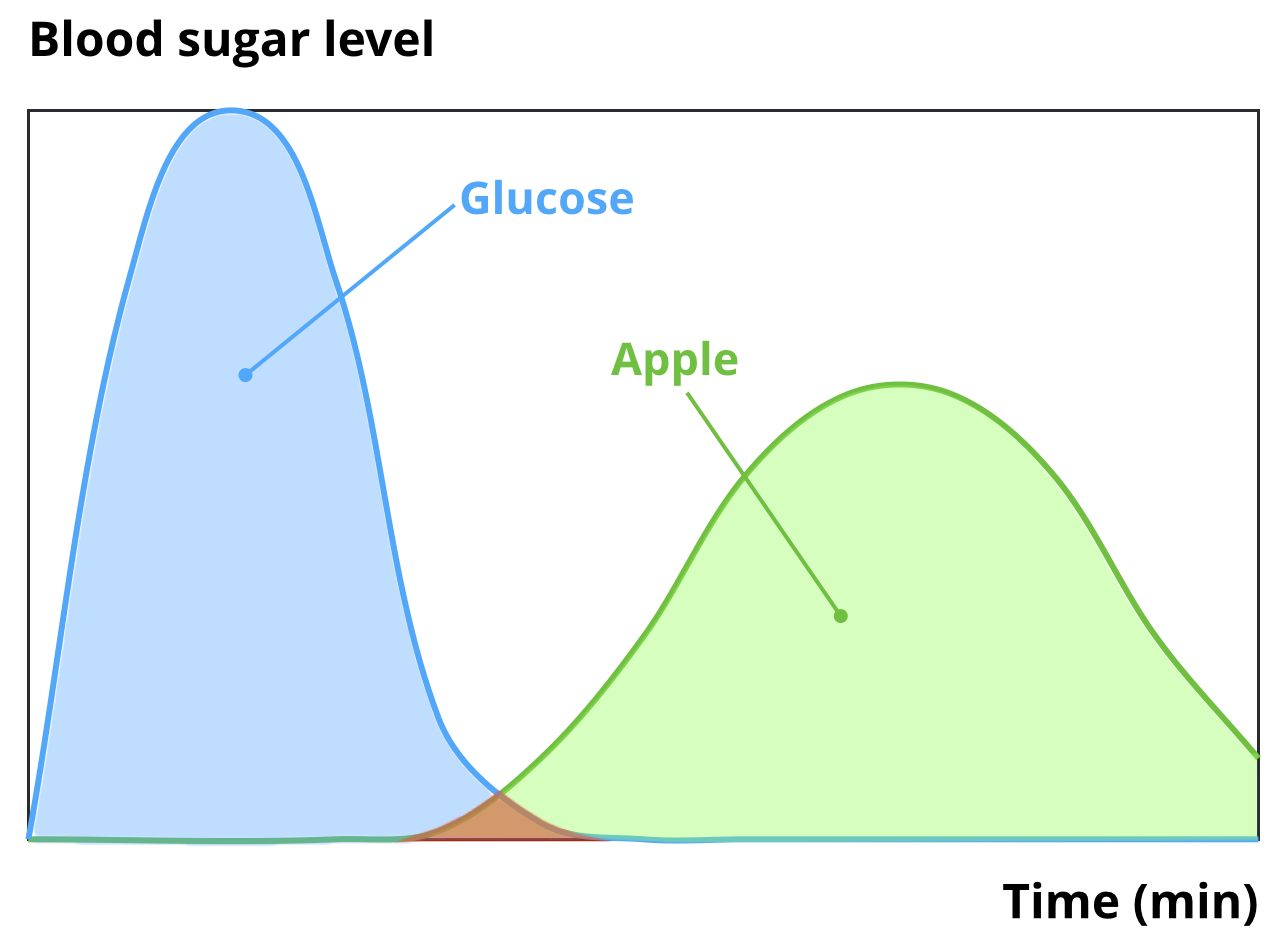

▲ Figure 1: Glucose passes into the blood far quicker than the sugars in an apple. For glucose consumption to aid the absorption of fructose, the two curves would have to overlap much more closely.

The above example illustrates that consuming pure glucose while eating a meal rich in fructose does not increase the body’s absorption of fructose in any meaningful way. This is because at the crucial stage when fructose is absorbed through the small intestine’s mucous membrane, the glucose has often already been completely absorbed. It can barely, or not at all, support in the absorption of fructose from other foods. As their manufacturers’ labels advertise, glucose tablets, taken in large quantities or small, are indeed “Fast-Acting”.

Even with a sugar solution consisting of equal parts glucose and fructose, people who suffer problems with bowel functions can still experience digestive problems [7]. The lower the glucose dose in relation to fructose [8], the worse those problems are. It is practically impossible to accurately dose pure glucose at a given time because it is digested so quickly. Furthermore, the glucose has no influence on the absorption of other poorly digestible carbohydrates or sugar alcohols, such as lactose, fructans and sorbitol [9].

It is therefore a good idea when planning meals that you have an even ratio of glucose to fructose and exclude poorly digestible compounds such as sorbitol. Glucose powder is not a reliable solution to alleviate digestive problems.

Back to blog

Sources:

[1] R. Gitzelmann et al., Essential fructosuria, hereditary fructose intolerance, and fructose-1,6-diphosphatase deficiency, The metabolic basis of inherited disease, McGraw-Hill, New York (1983), 118–140

[2] F. Kong et al., Disintegration of Solid Foods in Human Stomach, Journal of Food Science 73:5 (2008), 67–80

[3] K. Foster-Powell et al., Internationaltable of glycemic index and glycemic load values, The American journal of clinical nutrition Vol. 76:1 (2002), 5–56

[4] M. Ledochowski, Klinische Ernährungsmedizin, Springer-Verlag, 2010

[5] F. Heritage, Composition and Facts about Foods and Their Relationship to the Human Body, Health Research Books, 1971

[6] K. Englyst et al., Carbohydrate bioavailability, British Journal of Nutrition Vol. 94:1 (2005), 1–11

[7] C. Tuck et al., Adding glucose to fructose reduces breath hydrogen but not symptoms in fructose malabsorbers with a functional bowel disorder, Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism Vol. 4 (2016), p.28

[8] C. Kneepkens et al., Incomplete intestinal absorption of fructose, Archives of Disease in Childhood 59 (1984), 735–738

[9] L. Beaugerie et al., Glucose Does Not Facilitate the Absorption of Sorbitol Perfused In Situ inthe Human Small Intestine, The Journal of Nutrition Vol. 127:2 (1997), 341–344

Glucose can improve the absorption of fructose in the small intestine – in theory

Numerous studies confirm that consuming glucose at the same time as fructose leads to better absorption of the fructose [1]. Pure fructose alone is absorbed very slowly in the small intestine and can therefore reach the large intestine in high amounts, where it is broken down by microorganisms. By contrast, with a sugar solution that consists of equal parts fructose and glucose, the former can be absorbed through the intestinal wall much more quickly.

Common to each study, however, is that they involve pure sugar solutions, which the participants drink on an empty stomach. These conditions are necessary to ensure good comparability among the participants, but they are unrealistic when it comes to assessing glucose’s impact on fructose absorption in everyday meals.

What happens when food containing fructose is digested?

Let us use the example of an apple to take a closer look at the digestive process. After consumption, the apple passes through various stages of the digestive tract, in order for the body to extract as many of its nutrients as possible. Digestion begins as soon as the apple is chewed, as enzymes in our saliva break down the carbohydrates. Crudely chopped and chewed up by the time it reaches the stomach, gastric acid containing further digestive enzymes then turns the apple into a fine pulp.

The pulp passes through the pylorus and reaches the small intestine, where it is mixed with more digestive fluids that break down proteins and fats. Moving slowly through the small intestine, yet more nutrients are gradually absorbed through the intestinal mucosa into the bloodstream. Other enzymes in the intestinal mucosa break down disaccharides into their individual components – glucose, galactose or fructose – that can also then be absorbed into the blood (for more on this subject, check out our blog here).

Why do we care so much about this topic?

We have been developing our price-winning "Food Intolerances" app since 2011 and we are happy to share our knowledge with you. Check it out:

We have been developing our price-winning "Food Intolerances" app since 2011 and we are happy to share our knowledge with you. Check it out:

Food is digested at different speeds

Foods pass through the digestive tract at different speeds, depending on how easily they can be broken down. For example, a piece of white bread, which is easily digestible, passes through the stomach much quicker than foods containing fats and protein. Meanwhile, beverages containing sugar pass through the stomach quickly, and the sugars they contain are then promptly absorbed by the body in the intestines. With high-fiber foods, the pulp spends more time in the stomach and its carbohydrates are released steadily over a longer period of time. The pylorus permanently ensures that enough broken-down food fragments pass into the small intestine [2].

A comparison of the glycemic index of apple and glucose

The glycemic index is a scale from 1 to 100 that indicates how quickly a specific quantity of carbohydrates increases blood sugar levels after consumption. A high value signals a rapid increase.

| Food | Glycemic index |

|---|---|

| Glucose | 100 |

| Apple | 38 |

When determining a food’s glycemic index, glucose, having a value of 100, serves as reference point. As a monosaccharide, it is easily digestible and passes quickly into the blood stream. The digestion of a glucose tablet begins when it is chewed, since it is absorbed by the body through the oral mucosa. As glucose contains no fiber, it moves through the stomach in a matter of minutes. The absorption is complete soon after the glucose reaches the small intestine, where it travels barely an eighth of the intestine’s 8m length before passing through the intestinal mucosa and into the blood [4].

The apple is also easily digested because it contains very few fats and protein, but it passes from the stomach into the small intestine more gradually, over a period of two to three hours [5]. Its sugars are bound in a complex fiber structure, so they remain intact as the apple moves through the digestive tract, and they are released more slowly compared to pure glucose [6]. The fructose in the apple will not be completely absorbed even after it has passed through the small intestine, so a certain amount will reach the large intestine. If a sizeable quantity of fructose reaches the large intestine, digestive problems may occur.

▲ Figure 1: Glucose passes into the blood far quicker than the sugars in an apple. For glucose consumption to aid the absorption of fructose, the two curves would have to overlap much more closely.

Conclusion: simultaneous consumption of glucose for fructose intolerance is not generally effective

The above example illustrates that consuming pure glucose while eating a meal rich in fructose does not increase the body’s absorption of fructose in any meaningful way. This is because at the crucial stage when fructose is absorbed through the small intestine’s mucous membrane, the glucose has often already been completely absorbed. It can barely, or not at all, support in the absorption of fructose from other foods. As their manufacturers’ labels advertise, glucose tablets, taken in large quantities or small, are indeed “Fast-Acting”.

Even with a sugar solution consisting of equal parts glucose and fructose, people who suffer problems with bowel functions can still experience digestive problems [7]. The lower the glucose dose in relation to fructose [8], the worse those problems are. It is practically impossible to accurately dose pure glucose at a given time because it is digested so quickly. Furthermore, the glucose has no influence on the absorption of other poorly digestible carbohydrates or sugar alcohols, such as lactose, fructans and sorbitol [9].

It is therefore a good idea when planning meals that you have an even ratio of glucose to fructose and exclude poorly digestible compounds such as sorbitol. Glucose powder is not a reliable solution to alleviate digestive problems.

Why do we care so much about this topic?

We have been developing our price-winning "Food Intolerances" app since 2011 and we are happy to share our knowledge with you. Check it out:

We have been developing our price-winning "Food Intolerances" app since 2011 and we are happy to share our knowledge with you. Check it out:

Share article

Share article

Back to blog

Sources:

[1] R. Gitzelmann et al., Essential fructosuria, hereditary fructose intolerance, and fructose-1,6-diphosphatase deficiency, The metabolic basis of inherited disease, McGraw-Hill, New York (1983), 118–140

[2] F. Kong et al., Disintegration of Solid Foods in Human Stomach, Journal of Food Science 73:5 (2008), 67–80

[3] K. Foster-Powell et al., Internationaltable of glycemic index and glycemic load values, The American journal of clinical nutrition Vol. 76:1 (2002), 5–56

[4] M. Ledochowski, Klinische Ernährungsmedizin, Springer-Verlag, 2010

[5] F. Heritage, Composition and Facts about Foods and Their Relationship to the Human Body, Health Research Books, 1971

[6] K. Englyst et al., Carbohydrate bioavailability, British Journal of Nutrition Vol. 94:1 (2005), 1–11

[7] C. Tuck et al., Adding glucose to fructose reduces breath hydrogen but not symptoms in fructose malabsorbers with a functional bowel disorder, Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism Vol. 4 (2016), p.28

[8] C. Kneepkens et al., Incomplete intestinal absorption of fructose, Archives of Disease in Childhood 59 (1984), 735–738

[9] L. Beaugerie et al., Glucose Does Not Facilitate the Absorption of Sorbitol Perfused In Situ inthe Human Small Intestine, The Journal of Nutrition Vol. 127:2 (1997), 341–344

![[Blog]](../../rw_common/images/baliza_logo_retina.png)